200 years ago, Lord Byron, John Polidori, Percy and Mary Shelley shared a lugubrious evening at Villa Diodati. Ideas emerged from this evening that would become novels, such as Frankenstein and which initiated the trope of the mad scientist.

200 years ago, Lord Byron, John Polidori, Percy and Mary Shelley shared a lugubrious evening at Villa Diodati. Ideas emerged from this evening that would become novels, such as Frankenstein and which initiated the trope of the mad scientist.

“There is no great invention, from fire to flying, which has not been hailed as an insult to some god”

J.B.S. Haldane

Two hundred years ago, Lord Byron, John Polidori and Percy y Mary Shelley spent a lugubrious evening at Villa Diodati, a manor house on the banks of Lake Lemán. The eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia had covered the sky with a thick layer of ash that concealed the sun. The climate reflected the moral decline of Europe, after the Napoleonic wars, and the sensation that brilliant ideas of Illustration had lost the fight. In this turbulent climate, the only thing the writers could do was to shut themselves in and share horror stories by the fire. This encounter saw the start of works like Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus, a classic of 19th century literature and a pillar of western culture.

The exhibition Terror in the laboratory: from Frankenstein to Doctor Moreau celebrates the anniversary of this evening and tracks the origin of great subjects of science fiction that are still in force today: robotics, genetics and artificial intelligence are still heard in fields of scientific research. In many cases, these controversial issues have deep roots in this Faustian image of the scientist, like the last image of Adam, who received the punishment of expulsion from Paradise, for seeking knowledge. Authors such asShelley, Stevenson, Wells, Hoffmann and Villiers de l’Isle Adam created everlasting works that would immortalize the debate.

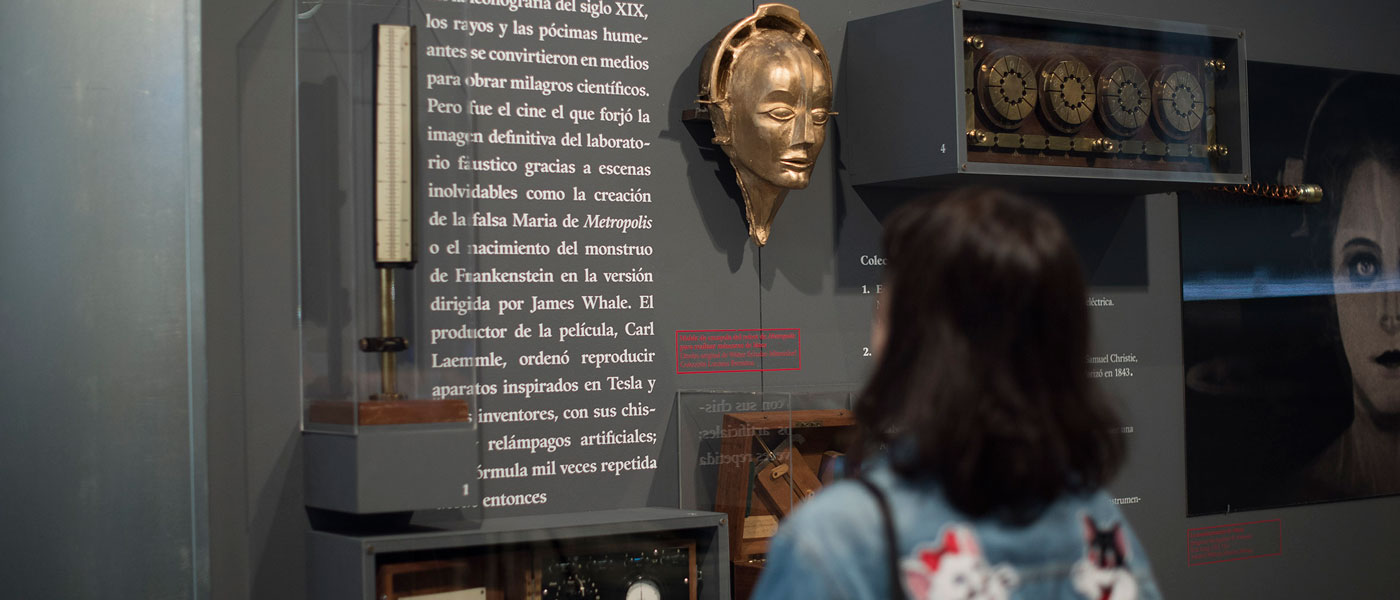

We start with the laboratory, as a place of creation where the deranged scientist plays at being God, with terrifying results incarnated in an anthropomophic creature that may be a monster , his double or a robot.

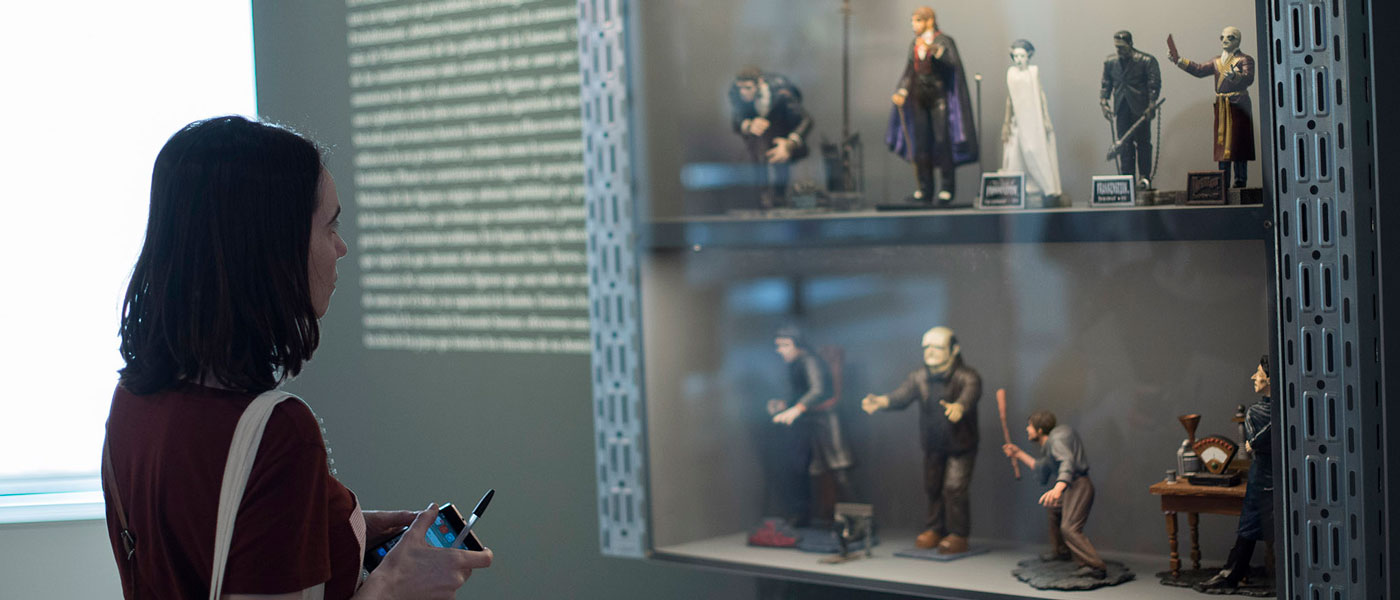

Under the curatorship of Miguel A. Delgado and María Santoyo, the exhibition analyses the true background behind literature. It explores the iconographic diversion of monsters and the creations of mad scientists in popular, pulp and underground culture since the sixties. To explore all these branches, the exhibition has original pieces from the Spanish Film Library, Complutense Museums and several unpublished private collections that can be seen on the second floor of the Espacio Fundación Telefónica from 16 June until the end of October.

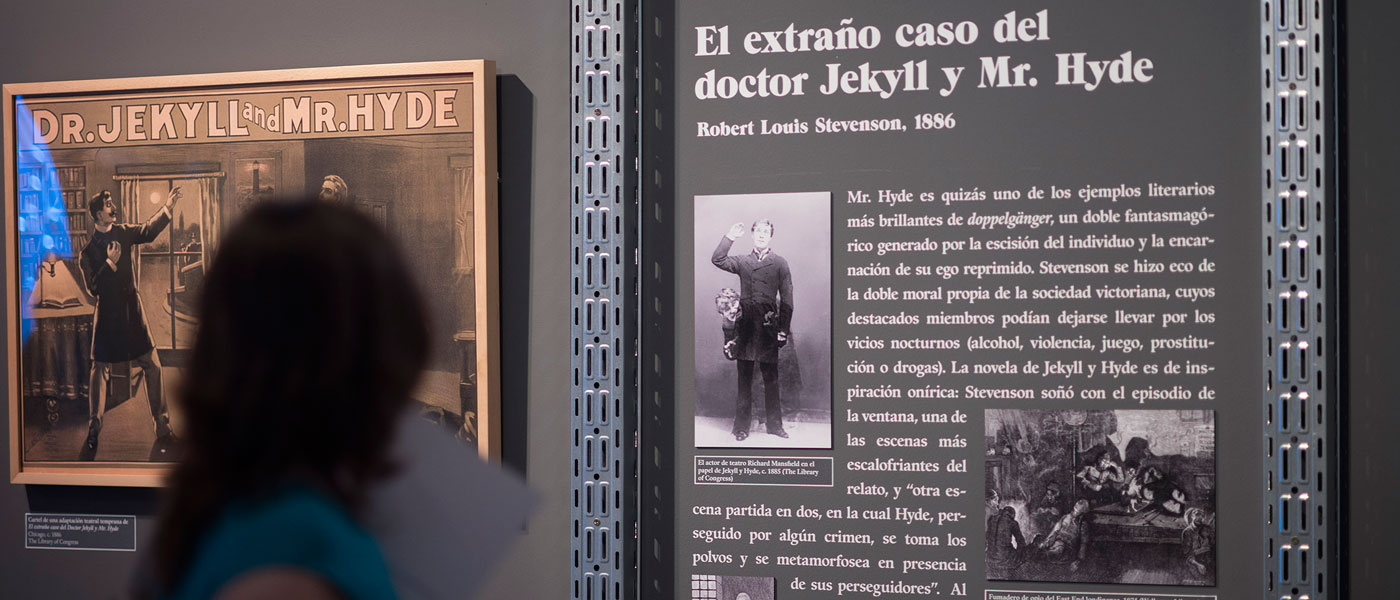

Terror in the laboratory: from Frankenstein to Doctor Moreau takes a deep look at six books divided into three blocks: the monster (Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley and The Island of Doctor Moreau by H.G. Wells), the double (The Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson and The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells) and the robot (The Sandmanby E.T.A. Hoffmann and The Future Eve by Auguste Villiers de L’Isle-Adam). These books give us a panorama of the great themes of the 19th century.

The monster

Many horror stories emerged as a result of that evening at Villa Diodati, but none have left such a footprint as Frankenstein. The pioneer novel by Shelley contemplated the analogy between the scientist and the divine creator, combining Gothic horror with modern science fiction approaches. In Frankenstein an essential figure was conceived in literature and popular culture: the demented scientist, the crazy doctor, the mad doctor.

At the start of the 19th century, chemistry and electricity were two developing sciences that appeared capable of answering an age-old question: what is the nature of life? Mary Shelley was not alien to these schools of thought . Her work was inspired both in the myth of Prometheus, in Paradise Lost by Milton, in the experiments of Luigi Galvani with electricity on muscles, and on the reflections of Erasmus Darwin on the resuscitation of dead microorganisms.

However, the novel has an underlying story and it is deeply moralistic, as the Prometheus audacity of Victor Frankenstein leads to terrible consequences. The creation of artificial beings is an extraordinary invention for some and offensive for others. A debate of deep legendary and literary roots that are still present in biogenetic laboratories.

Vivisection was also widely used in scientific reports of the 19th century. The practices of François Magendie and Claude Bernard led to protest, but their discoveries laid the foundations of experimental physiology. Thinkers such as Jeremy Bentham and Schopenhauer showed their rejection, while Darwin had doubts on whether vivisection could be tolerated. The Island of Doctor Moreau, by H.G.Wells, proves that it was not achieved and the question is still discussed today.

The Double

The Double, the German doppelgänger, the evil twin. Romanticism took particular interest in the phenomenon of the double, as the materialization of the dark and mysterious side of the human being (what Jung would call, the shadow). This interest led to iconic protagonists in several science fiction works and in fantasy literature.

In 1886, Robert Louis Stevenson published The Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. This is one of the most brilliant literary examples of the doppelgänger, a phantasmagorical double produced by a split in an individual and the incarnation of his repressed ego. Stevenson reflected the use of double standards, whereby prominent members of the Victorian society could be carried away by evil vices (alcohol, violence, gambling, prostitution or drugs). In 1897, H.G. Wells published The Invisible Man, one of the chief novels of science fiction. In The Invisible Man2>, Wells attempts to outline a "realist" method: not to be restricted only to transparency, but also to manipulate refraction.

The Robot

The storyteller E. T. A. Hoffmann turned to the figure of the mechanical android for the first time, in his short story Automata, published in 1814. However the machines he describes refer to famous automatons manufactured by Jacques de Vaucanson and Wolfgang von Kempelen in the 18th century. Romanticism recovered the interest in this tradition and its supernatural derivations, alchemical achievements such as the "Iron Man" by Albertus Magnus, or the "Brazen Head" by Roger Bacon. In The Sandman, the automaton Olympia is described as a semi-magical creature, a device that is indistinguishable from a human being, but without a soul, a living puppet.

The 19th century saw a variant of the robot: the artificial woman. The real Edison tried to carry out, on a small scale, what the fictitious Edison achieved (as a fictional character) in The Future Eve: to construct a machine able to accuratorly reproduce the aspect and behaviour of humans . In this case they were talking dolls. They were to be marketed, but suffered a resounding failure, as the dolls were frightening owing to their sinister aspect of toys, with voices similar to psychophony emerging from their chest. In another, totally different field, the introduction of rubber and other soft, flexible materials was used to manufacture erotic toys, including complete female bodies. Everything was done to achieve the fantasy of a fully submissive and receptive woman, to satisfy any sexual whim. This was the latest myth represented by the android Hadaly de Villiers, available in "pornographic technology" catalogues, in the words of the sexologist Iwan Bloch. The symbolist science fiction novel written by the French author, Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam and published in 1886, is also well-known for popularizing the term android.