A fascinating journey that starts at the dawn of sound recording with equipment such as Scott de Martinville's phonautograph and Thomas A. Edison's phonograph.

A fascinating journey that starts at the dawn of sound recording with equipment such as Scott de Martinville's phonautograph and Thomas A. Edison's phonograph.

The history of recording music and its reproduction over the course of time. This project portrays the happy encounter between music and technology in the mid-19th century, the huge technical advances in recording and playing music that have taken place since then, and how these have changed the way we create, listen to, feel and share music.

A story that speaks to us of human curiosity and the persistent search for ways in which to capture the beautiful melodies of an art form which, in essence, was enjoyed ephemerally.

A moving story, curated by Cristina Zúñiga, from the arts team at Fundación Telefónica, beginning at the dawn of sound recording with equipment such as Scott de Martinville‘s phonautograph and Thomas A. Edison‘s phonograph, running parallel to such paradigmatic landmarks as the tape recorder, the compact cassette and the Discman, and culminating in the more recent playback devices such as mp3 players.

The exhibition is organized around three main areas corresponding to the chronological development of the devices and supports. The first section, Origins, covers the years between 1857 and the first decades of the 20th century>; next is the Sound Revolution, from the 1930s to the 1990s and lastly, Digital Sound, from 2000 up to the present day. The show is rounded off with a series of related items including patents, technical drawings, photographs, recordings, posters, audio-visual material and more.

As the exhibition demonstrates, this constant technological progression would have immediate repercussions on culture and society, giving rise to significant changes both in the way music was created, produced and consumed and in the music industry itself.

The exhibition ‘1, 2, 3… Recording!’ can be visited from 21 October 2016 to 22 January 2017, on the fourth floor of the Espacio Fundación Telefónica.

Origins, from 1857 through to the first decades of the 20th century

The history of sound recording began in 1857 when the Parisian typesetter and inventor Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville (1817-79) built a piece of equipment that he named the phonautograph, which permitted sound waves to be recorded onto smoked paper. That was how an acoustic sound was recorded on a storage medium for the very first time. Although it was conceived as a visual tool for the study and analysis of sound, Martinville imagined various other uses, aware of the importance of his invention as a testament to the talent of “those great artists who die without leaving behind the slightest trace of their genius”.

The phonoautograph did not, however, play back recorded sound, a breakthrough that came about with the appearance, in November 1877, of the next technological landmark, the phonograph by Thomas Alba Edison (1847-1931). This was one of the most important advances that would completely transform the way music was created and experienced, without that being the original intention of its creator. The phonograph was conceived, amongst other functions, for the purpose of dictation – audio-books for the blind, practising correct elocution, “family recordings”, records of memories, maxims, advice and the last words of family members – all in addition to the playing of music.

It was Emile Berliner (1851-1929), a German-born engineer, who was destined to take the definitive step towards a new era of sound when, in 1887, he patented the gramophone, a sound recording device on a flat disc. Berliner’s first appliances could only perform one function, meaning that the processes of recording and playback required two different pieces of equipment, a fact that did nothing to prevent their popularity, the generation of demand and international expansion. Moreover, the discs were more resilient than cylinders and easier to store and transport. The space in the middle of the disc could be used for credits and information about the piece and the company, something that was not possible with cylinders.

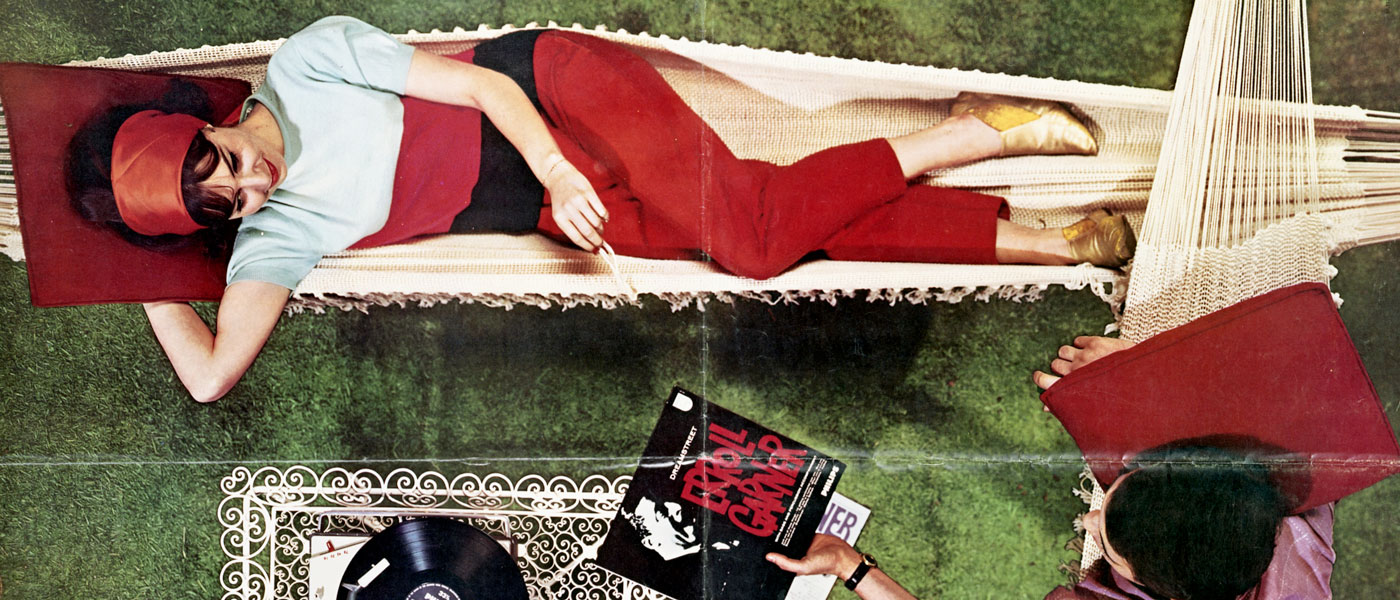

These technological advances brought with them significant changes in the way music was composed, performed and produced as well as its public consumption. With the first sound recording and the possibility of playing it back, music was no longer a one-off and unrepeatable art. There was no longer any need to go to the opera house or to concert halls. Now, music could be enjoyed anywhere, with the option of listening to the same pieces over and over again. Musical experience became more diverse; it was no longer only a collective art form in a public space but could also be enjoyed individually in private, at home.

Sound Revolution

It would not be until 1925 that sound recording and playback became an electronic process, thus bringing to an end the so-called acoustic era. Applying electricity to gramophones and improvements in microphones led to a transformation in the old world of music at all levels.

From a marketing and consumer perspective, the contribution of Berliner and his flat discs was fundamental. The German-born engineer was not only an enormously talented inventor, he also displayed considerable business acumen, as demonstrated in his initiative to mass-produce discs based on a mould, enabling him to lay the foundations of the business model for reproducing music (record companies). It led to a new type of entertainment, music at home, which at the same time generated millionaire revenues for the growing record industry.

From a marketing and consumer perspective, the contribution of Berliner and his flat discs was fundamental. The German-born engineer was not only an enormously talented inventor, he also displayed considerable business acumen, as demonstrated in his initiative to mass-produce discs based on a mould, enabling him to lay the foundations of the business model for reproducing music (record companies). It led to a new type of entertainment, music at home, which at the same time generated millionaire revenues for the growing record industry.

Technical advances followed both in the format –the record– and in the sound reproducer –the record player or turntable-: the disc evolved from Berliner’s primitive wax-coated versions, through those made of slate, rubber, vulcanite, celluloid and Shellac lacquer until ending up with vinyl. One of the main innovations was the microgroove – the groove being three times narrower, the capacity per millimetre higher and the sound quality better – which, when perfected, led to the appearance of the LP or long-playing record, at 33 rpm, launched onto the market by Columbia Records in 1948. The record player, as we would recognise it, appeared in 1925 and differed from the gramophone in that it was entirely electric, both for operating the turntable and capturing the sound.

Oberlin Smith (1840-1926), an American engineer, came up with and published an idea for designing a device, the telegraphone, for magnetic recording. By not patenting his idea, Smith left the door open for other scientists and engineers to research how to capture sound magnetically. Ten years later, Valdemar Poulsen (1869-1942), a Danish telecommunications engineer, invented the first magnetic recording system onto wire.

The step from wire to magnetic tape was taken by the German engineer Fritz Pfleumer (1881-1945), who in 1928 coated paper tape with iron oxide to create a “recording tape” and came up with the first tape recorder, which he called “soundingpaper” or the “Sound Paper Machine”. In 1934 the German company AEG (Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft), created the magnetophon and a year later they presented the model K1 at the Berlin Radio Show, the forerunner of the modern device.

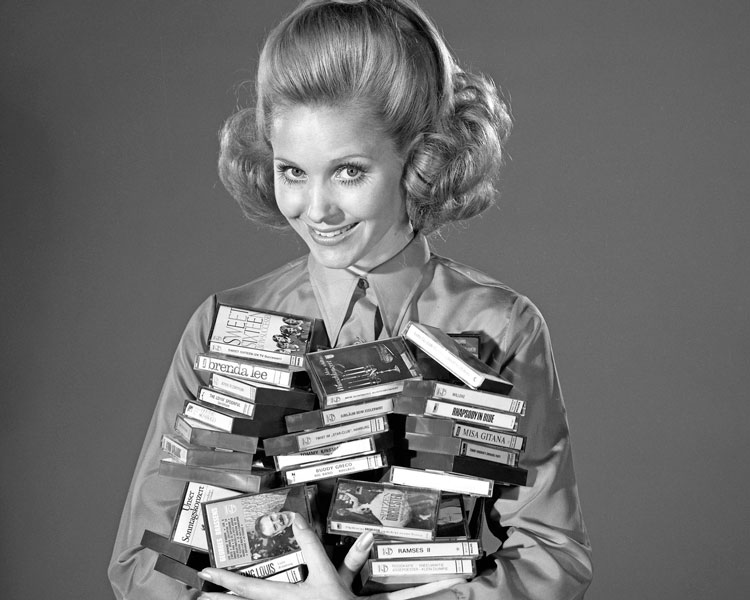

In 1963 the Dutch company Philips launched the first compact cassette on the market, with a royalty-free patent in order to popularise its use and convert it, as duly occurred, into the international standard format.

The objective of making a simple, compact, light and low consumption device was achieved in 1979 with the launch of the Sony TPS-L2, the first stereo player with headphones, perhaps better known by its commercial name, the Sony Walkman. The Walkman marked a definitive change in the way people listened to music. The compact disc, developed jointly by Philips and Sony in 1982, provided the added value of advanced technology applied to sound. The first compact disc player was the Sony D-50, known as the Discman.

The compact disc experienced a decade of advances with optical disc systems, digital reproduction and data, music and video storage: CD-ROM, CD-R, CD-RW, DVD and, more recently, Blu-ray.

Digital Sound

At the same time as compact discs and players were enjoying great success, a group of German scientists led by Karlheinz Brandenburg (1954), director of digital media technology at the Fraunhofer IIS Institute, had already been working since 1987 on a means of transmitting audio in a compressed digital format. The uncompressed audio signals from a CD consume large quantities of data and are therefore not suitable for storage and transmission. Brandenburg and his team developed a series of patents with algorithmic technology being approved in 1992 by the Motion Picture Experts Group (MPEG). This was how the third level of MPEG1 compression came about, the MPEG-1 Audio Layer 3 or MP3. In July 1995, for the very first time, Brandenburg used the extension .mp3 on his computer.

The first mp3 player was the MPMan F10, created for the Korean firm Saehan Information Systems and commercialised in 1998.

But the real revolution came through the internet. The creation of file-sharing software called P2P (peer-to-peer), the rise of platforms such as, to begin with, Napster (end of 1999) and then later MySpace, iTunes, Kazaa, Spotify and Deezer, along with applications and software for creating music -Garage Band, Cubase, Logic, Protools, etc. – would open the doors for fans, music-lovers, consumers and even musicians themselves into a new world, unknown to begin with but full of promise.

The technological progress of computers, tablets and smartphones, the affordable cost of certain models and its high popularity amongst consumers has facilitated the wider accessibility of music which now reaches virtually every corner of the planet with unprecedented means of sharing it.

This is the perspective right now and, just like 150 years ago, we don’t know what will happen next or how music will be composed, listened to or shared. It could even be the case that vinyl and cassettes, nowadays enjoying a revival, are back with us to stay, both claiming their place based on our nostalgia for the lost analogical sound and our pleasure in owning items of great sentimental value. Let’s see.

Programme of workshops

The exhibition‘1, 2, 3… Recording!’ is supported by a programme of workshops prepared by our education team. There are workshops suitable for all ages and registration is free.

Parallel activities

During the months of the exhibition, our auditorium will host a number of talks and activities related to the show. Keep checking this website and our social networks to keep abreast of everything.

The day before the exhibition opens to the public, starting at 19:00, there will be the inaugural session with the curator Cristina Zúñiga, from the Fundación Telefónica’s exhibition team; Laura Fernández, head of collections and exhibitions at Fundación Telefónica; the music journalist Diego A. Manriqueand the music producer Paco Trinidad. After this session the exhibition will be freely available to visit.