Did you think that Telefónica’s technological heritage only comprised switchboards, telephones or different types of cabling? Then think again: among the more than 10,000 objects in our collection there are some really rare pieces; hundreds of different items with diverse uses, some of which are even quite difficult to identify, all associated with the world of telecommunications.

Did you think that Telefónica’s technological heritage only comprised switchboards, telephones or different types of cabling? Then think again: among the more than 10,000 objects in our collection there are some really rare pieces; hundreds of different items with diverse uses, some of which are even quite difficult to identify, all associated with the world of telecommunications.

The Rarities Collection exhibition aims to shine a spotlight on these other pieces – unknown, yet absolutely necessary in the complex system of establishing and improving telephone communications over the decades.

They might look odd or unique and sometimes even quite attractive, but what the objects displayed in this room aim to reveal is the number of people and the level of specialist work involved in the intricate web of telecommunications. They also illustrate the unusual methods – some of which have now vanished – of certain jobs and the history of technology at each given time.

This little journey through certain pieces from Telefónica’s historical and technological heritage also serves as food for thought on the need to preserve and document part of our history. The fact is that to be able to put on this exhibition it was essential to refer to the archived documentation. The tasks carried out painstakingly by the Testing Laboratory (from 1926 through to the present day) and the manuals, certificates and newsletters published by Telefónica from the 1920s demonstrate the company’s interest in putting everything in order, standardizing working procedures and creating a business culture which, with hindsight, shows how very advanced we were for those times.

We can now enjoy these objects that illustrate meticulous, painstaking work, the innovations in the telephone service and, most importantly, the history and the evolution of technology in our country.

IT’S ALL CHECKED: THE GENERAL TESTING LABORATORY

In 1926, just two years after it was established, Telefónica set up its General Testing Laboratory. It was fundamental for the company to be able to check the quality of the materials involved in its work. The laboratory started out with three departments: chemicals, mechanics and electricity, and over the years, as well as conducting analyses and tests, it also came up with solutions and working improvements as it was responsible for checking the specifications and construction models established by the company and sending its technicians and employees to carry out the company’s numerous installations. Many of the pieces on display in this exhibition were analysed by the General Testing Laboratory.

The General Testing Laboratory became a real centre of research on and verification of the conditions and properties of materials. The exhibition shows two items that were used in the early 20th century – a rheostat and a microscope.

The rheostat was used to conduct electrical tests and analyses. It allows the intensity of the current to be regulated, either increasing or decreasing the resistance to move the shaft. In an electrical circuit, the higher the resistance, the slower the current, and vice versa. They also checked wires and cables, handset cords, the insulators used in telephone posts, and much more.

The microscope studies were hugely important when it came to selecting the right material for each purpose. These were carried out on metals in general as well as on insulating papers, wood, etc. We still have microscope studies on the metal caps used on the public highway and on telephone posts, amongst other uses, to determine their resistance and potential deterioration.

ON MY HONOUR: TELEPHONE SPLICERS AND LINEMEN

To be able to reach the category of Splicer or Lineman at Telefónica, the first thing a candidate had to do was join a working crew and carry out simple, non-specialist installation tasks: fitting posts, digging holes, etc. Meanwhile, working alongside the splicers or linemen gave them the necessary theoretical and practical knowledge.

They also had to know how to read and write; have rudiments of geography; be able to solve mathematical operations with whole numbers and decimals; be familiar with the decimal metric system, and have notions of geometry. The company undertook to provide the textbooks and notes for this learning process. They also needed to meet certain physical attributes: they had to be able to climb posts with gaffs, lift a weight of 30 kilos with one hand to a height of one metre, and be at least 1.60 metres tall.

Once they had passed the exams, there was one final requirement. The categories of lineman and splicer were among those that were most directly affected by the secrecy of communications law. Consequently, before taking on these positions, all these employees had to make a solemn oath before the company managers.

The carbide lamp and candle-boxes shown in this display cabinet were part of the set of tools carried by the splicers.

The lineman became a very representative figure for Telefónica, often appearing in its internal publications as the hero of almost impossible repairs during blizzards, storms and floods. The images of these technicians clinging to the top of telephone posts to install the lines became an iconic identifying feature of the company’s work, especially in those first few years of the expansion of the telephone service across Spain.

They were also responsible for repairing any breakdowns and installing lines to individual homes, so their relationship with the general public became the public face of the company. Trained in the company’s academies, this became one of the collectives with the largest number of employees assigned to this category.

AND HOW DID IT WORK BACK THEN?

As you can see in one of the exhibition’s display cabinets – manually! Every month, on certain days, the technicians took photos of the switchboard meters which showed the consumption of each telephone number. The film was developed in the invoicing department which then issued the bills. In Spain this system was still in operation up to the 1990s.

AT THE HEART OF A SWITCHBOARD

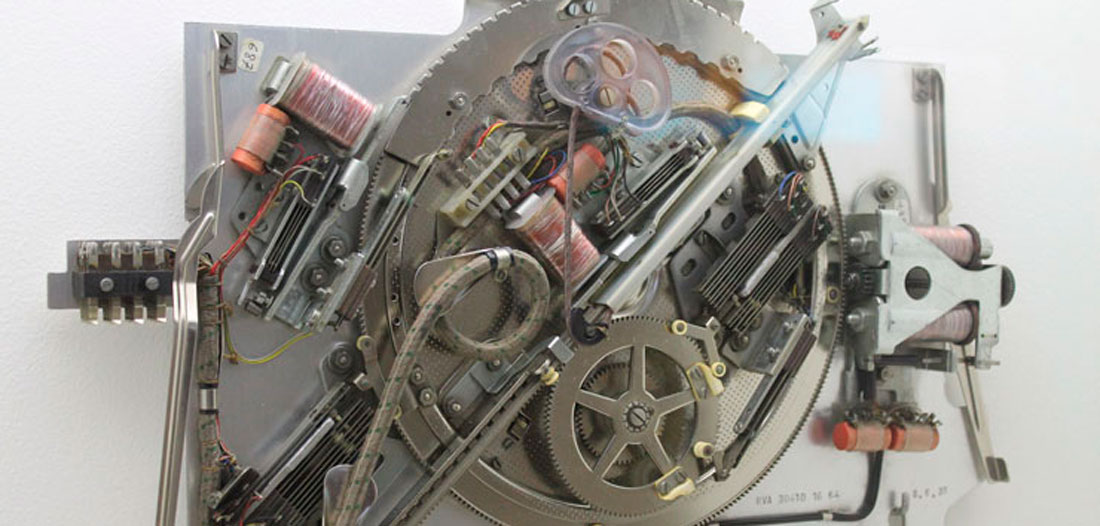

The parts displayed in another of the cabinets show the advances that have taken place in telephony to achieve ever-faster communications. One of the first advances in telephony was being able to establish calls automatically, without the need for manual switchboards. In the 1920s the installation of these automatic systems was a huge development and there were various different types and manufacturers: Rotary, AGF and Strowger, for example. In Spain, Telefónica opted for the Rotary system which turned out to be a real landmark in the company’s history.

But there was one switchboard with another system. In San Sebastian, in 1926, an AGF system manufactured by Ericsson was installed, the only one of this kind to operate in Spain. This was also a rotary system and its parts, laid out in horizontal trays, moved around until the requested numbers were selected.

AND WHAT IF SOMETHING WENT WRONG?

If there was a power cut, the telephone carried on working. This was thanks to the emergency systems and alternative power supply in the telephone switchboards. The batteries in the building immediately started providing the power necessary to keep the machines running. Mercury switches such as this one were used in the early Rotary 7A switchboards to activate the emergency systems.

Since its foundation in 1924, Telefónica has published regulations to avoid occupational accidents and has tested all the equipment necessary to protect the health and safety of its workforce in the Testing Laboratory. In the 1960s an analysis was made of the old masks that were intended for use in the switchboards. These masks were used to protect the workers from any smoke or potentially toxic gases that may have been given off, such as the burning of relay wires in a fire.

These rarities are from a collection of pieces selected from among the more than 10,000 items that make up Telefónica’s technological heritage.

The permanent exhibition of the History of Telecommunications: Technological Timeline of Telefónica, which is intended to provide information on the evolution of telecommunications with a particular emphasis on telephony in Spain, is displayed on the second floor of the Fundación Telefónica Space.