The fascination aroused by the red planet is the protagonist of this exhibition, which reflects on the possible arrival of man.

The fascination aroused by the red planet is the protagonist of this exhibition, which reflects on the possible arrival of man.

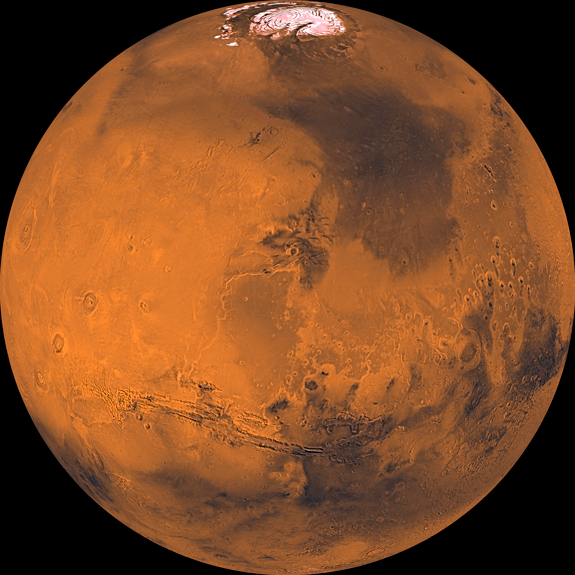

Throughout time and in many cultures, Mars has generated more curiosity and veneration than any other planet. A source of fear and fable at the same time, territory of “the others” and a destination yearned for by the man of the future, Mars represents, in the words of Carl Sagan, “a kind of mythic arena onto which we’ve projected our earthly hopes and fears”.

Walking on Mars is, without a doubt, the greatest challenge that mankind has proposed to bequeath future generations. A pipe dream for some, an urgent goal for others, the fact is that our arrival on Mars was strong fuel for the powerful driving force of human curiosity which often builds the future.

Visible like few other spots in the starry night due to its brightness and orange tint, since Antiquity Mars has inspired the curiosity of wise men and ordinary people. According to some historians, humankind has known about the red planet since 4500 years ago, when the Assyrians tried to register its strange trajectory.

This exhibition addresses the roots of this fascination, and its impact on culture and science, and explores some of the hypotheses for us to become the first interplanetary species.

“Mars. The conquest of a dream’ is divided into five large exhibition blocks:

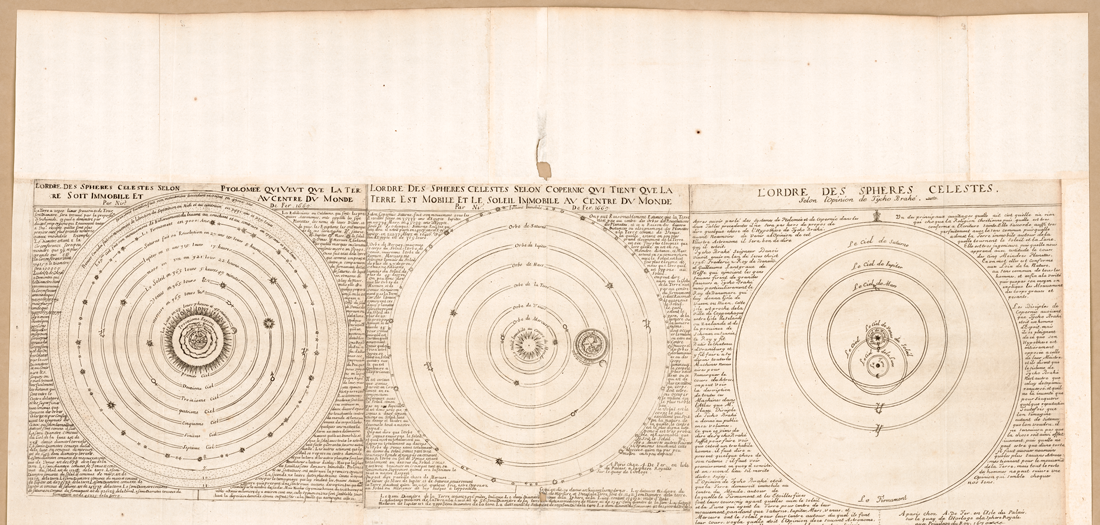

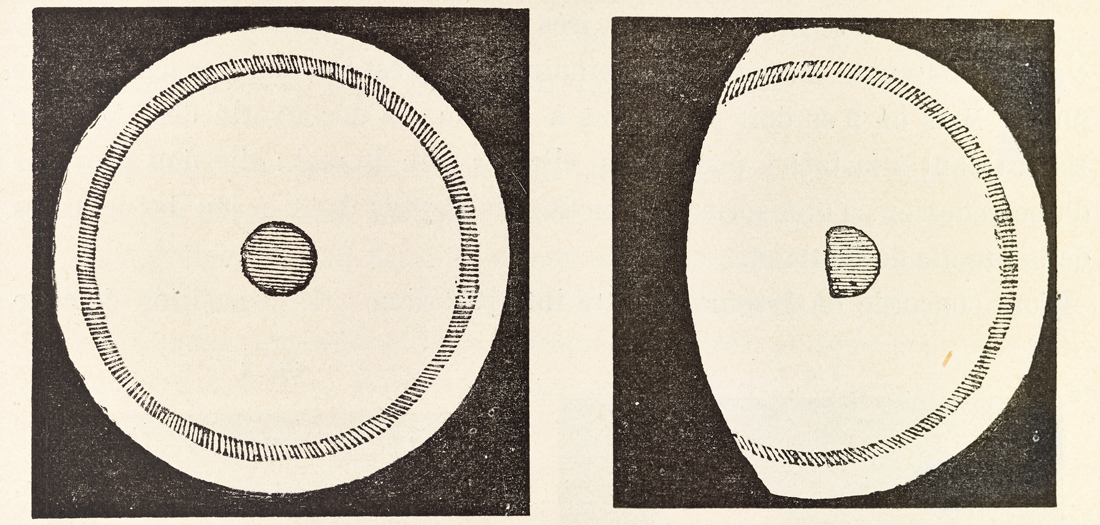

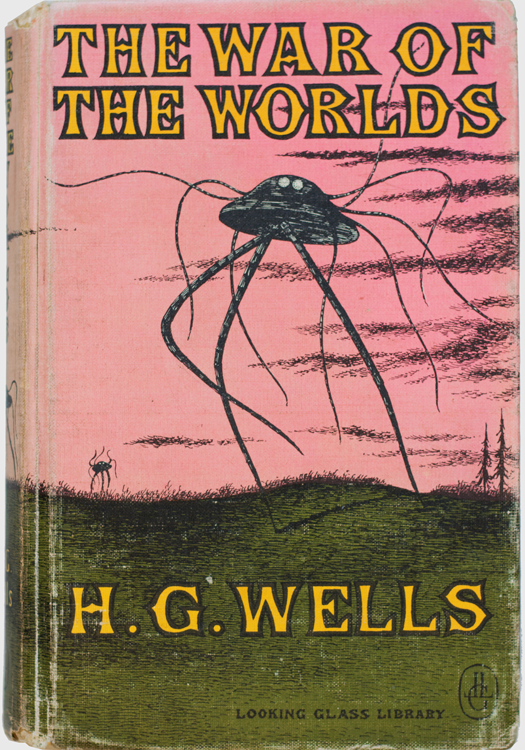

Mars. The conquest of a dream. An introduction to the origin of our fascination with the red planet; Looking towards Mars. The retrograde movement of Mars represented a disconcerting challenge for astronomers throughout history. Only when Copernicus found the key, and Kepler developed it, did the headaches come to an end; Mars in the imagination. The impact of Mars on culture (cinema, music, literature, etc.) and the evolution of the concept of Martians as a projection of the concerns of different eras and contexts; Towards Mars. All the milestones in the race to walk on Mars and On Mars. The red planet will be the next great mission for humanity. NASA expects to launch its first manned mission to Mars in the decade of 2030.

The exhibition -which can be visited on the fourth floor of the Telefónica Foundation Space– includes some pieces of great value due to their historical and documentary interest. Books and original prints from the Copernican Museum in Rome; a fragment of the Mars meteorite ZAGAMI, which fell on 3 October 1962 in Nigeria; original illustrations from ‘The War of the Worlds’ by Brazilian artist Henrique Alvim Corrêa (Brazilian, 1876-1910), a replica of Galileo Galilei’s first telescope, three 3D-printed models that recreate potential living spaces of colonies on the red planet; an immersive audiovisual piece that discovers the sunset on Mars from original NASA images.

Co-produced by the City of Arts and Sciences, Valencia Government, with collaboration from ESA, INTA, INAF and LG, the ‘Mars. The Conquest of a Dream’ exhibition can be visited from 8 November 2017 to 4 March 2018.

Why Mars

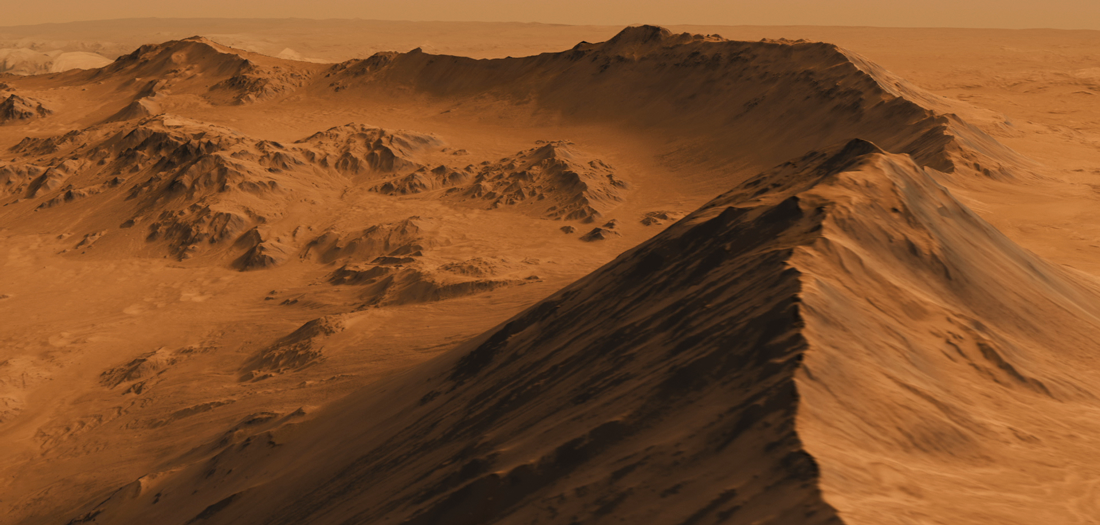

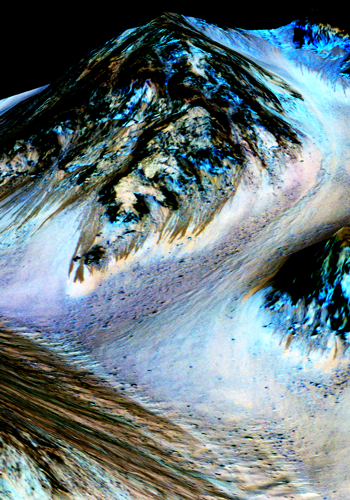

Besides being our nearest neighbour in the solar system, the reasons why we’ve always wanted to go to Mars are diverse and are based on both scientific and existential issues. Finding out whether life comes from Mars or whether we can find life on the planet, to understand why a planet with water became an arid desert at the mercy of cosmic radiation and to conquer a new space to enable us to become the first interplanetary species. Without a doubt, Mars seems to be one of the best positioned planetary candidates to host or have hosted some type of biological life. To find out if life ever arose on Mars to then maybe disappear later, or to discover if life could have reached Earth from another planet is part of what makes Mars a unique candidate for exploration.

Besides being our nearest neighbour in the solar system, the reasons why we’ve always wanted to go to Mars are diverse and are based on both scientific and existential issues. Finding out whether life comes from Mars or whether we can find life on the planet, to understand why a planet with water became an arid desert at the mercy of cosmic radiation and to conquer a new space to enable us to become the first interplanetary species. Without a doubt, Mars seems to be one of the best positioned planetary candidates to host or have hosted some type of biological life. To find out if life ever arose on Mars to then maybe disappear later, or to discover if life could have reached Earth from another planet is part of what makes Mars a unique candidate for exploration.

Mars in the Imagination

Mars is a projection of human concerns. The exhibition will study the impact of Mars on the collective imagination, on culture (cinema, music, literature, etc.) and the evolution of the concept of Martians as a projection of the concerns of different eras and contexts. The impact of Mars on the collective imagination.

Towards Mars/On Mars

On 14 July 1965, the Mariner 4 probe put an end to centuries of speculation about the red planet: the photographs it transmitted depicted an i nhospitable and hostile Mars, devoid of life. However, while the idea of an imaginary existence of strange beings started to become blurry, a dream of even greater proportions was born: walking on Mars.

nhospitable and hostile Mars, devoid of life. However, while the idea of an imaginary existence of strange beings started to become blurry, a dream of even greater proportions was born: walking on Mars.

During the first missions, the ships were only able to perform flyovers, as they tried to take as many photographs as possible as they passed by the planet. Technological advancements saw ships beginning to enter into orbit around Mars, enabling a more extended period of study. The next step was a “Mars landing” on the surface. At present, it is not only possible to land artefacts on Mars, but they can move around on the surface of the planet for years.

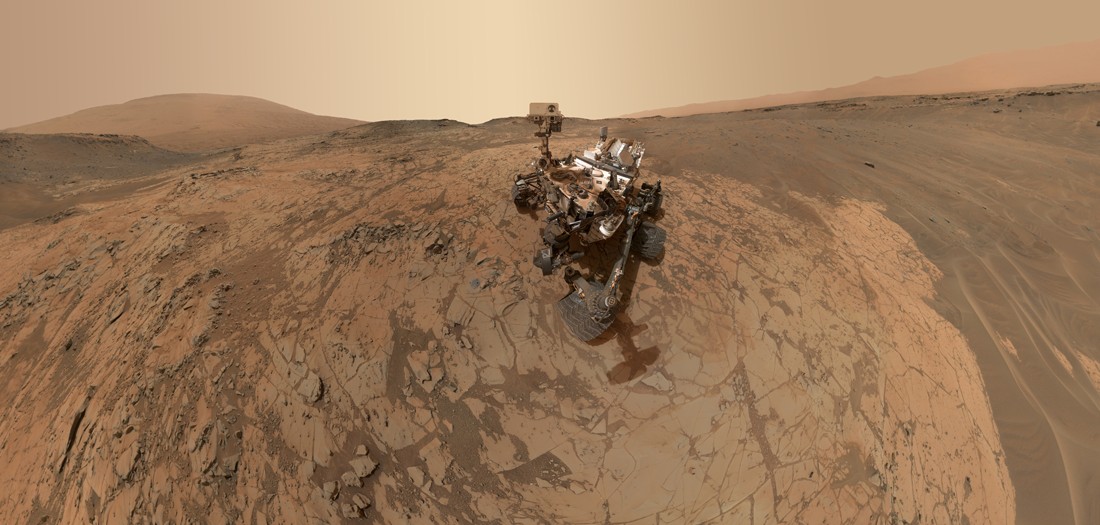

The turn of the century rekindled the race for Mars with a succession of unprecedented discoveries. The clear photographs from the Spirit and Opportunity vehicles allowed us to feel like we were there. Thanks to the Phoenix mission, we were able to descend several centimetres below the surface and the robot Curiosity —the heaviest human-made object successfully deposited on Mars’ surface— shared with us its selfie.

Some people foresee sending the first manned mission to Mars sometime in the 2030 decade while other still consider this an impossible feat. Regardless of what happens, the dream of becoming an interplanetary species continues to progress. The red planet will be the next great mission for humanity. Astronauts who venture into the exploration of our neighbour planet will have to embark on an uncertain, months-long journey and, in the best of cases, will have to face an environment that is tremendously hostile for human beings. NASA expects to launch its first manned mission to Mars in the decade of 2030. A utopia to some or an imminent reality to others, what is sure is that the challenges we will face are titanic in size.

A participatory experience

The ‘Mars. The Conquest of a Dream’ exhibition is a series of participatory pieces that generates open content and that involves social media as a means to attract community participation. Pieces that question and motivate visitors to actively participate with the installations, providing all the people who visit the fourth floor of the Telefónica Foundation Space with a different opportunity to be immersed in the exhibition space and to acquire greater knowledge of the objects that make it up. A quiz on images of Earth and Mars, including the option to take a ‘Martian selfie’ with the Curiosity vehicle and to discover its physical characteristics on the red planet to share on social media. In addition, visitors can also participate in developing a code of best practices by sending tweets about mistakes humanity has made on Earth that should not be repeated on Mars. The conclusions will be passed on to the space agencies. The pieces have been developed by the experimental and interactive editing Unit of the Valencia Polytechnic University (UPV).

Workshop program and parallel activities

- The ‘Mars. The Conquest of a Dream’ is accompanied by a workshop schedule organised by our educational team. There are workshops for all ages and registration is free of charge. View all the details here.

- In addition, we’re holding a competition for the Instagram community. We invite you to participate by sending images of the colour of Mars, or the Red Planet, as it is known. To participate, upload your image to Instagram with the hashtag #RojoMarte, from 22 October to 12 November, included.

Co-produced by: the City of Arts and Sciences, Valencia Government.

In partnership with: ESA, INTA, INAF y LG.