This exhibition pays tribute to Ángela Ruiz Robles (Doña Angelita), a Spanish schoolteacher who taught from the 1920s to the 1960s in Galicia; a woman ahead of her time who devoted a good part of her life to improving education.

This exhibition pays tribute to Ángela Ruiz Robles (Doña Angelita), a Spanish schoolteacher who taught from the 1920s to the 1960s in Galicia; a woman ahead of her time who devoted a good part of her life to improving education.

Doña Angelita, a Spanish schoolteacher who taught from the 1920s to the 1960s in Galicia, was a woman ahead of her time. Inspired by her creativity and passion for her work, she devoted a good part of her life to improving the education of young children through a series of educational publications and several very ingenious technological inventions. Being a working woman, widow and mother of three children in the Galicia of the 1950s proved no obstacle for the determined and innovative Doña Angelita to become an active inventor with several patents, most notably the Mechanical Encyclopaedia, today regarded as a precursor of the e-book. It was a device intended to update the obsolete teaching methods of that time, which were based on memory exercises, and to help students learn in a more active, individual and logical way.

A woman who refused to conform

The period in which Doña Angelita was a teacher, inventor, businesswoman and mother could be summed up in the question a journalist asked her during an interview in 1958: “Can a good inventor also be a good housewife?” The first 50 years of the twentieth century in Spain provide a litany of disheartening stories of women’s plight at that time.

When it came to education in the early 20th century in Spain, only 25% of the female population knew how to read and write and the female illiteracy rate was 60% higher than in men.

This was a society in which the role of women was practically non-existent, where women were mainly housewives with hardly the most basic education (and forget about higher education) whose access to the job market was limited to menial work in factories or, in the town of El Ferrol where Doña Angelita lived, as stevedores on the harbour wharves. This was a society in which, as a general rule, the most advanced technology was a radio and there was a dearth of the more common ‘technological’ elements of daily life such as cars, washing machines and so on.

Inventor and writer

Doña Angelita herself said that her interest in inventions started in 1916. Her interest in education and pedagogy and her determination to make learning easier were reflected in her numerous writings and, of course, in her inventions. She wrote and published 16 books, all of them dedicated to education and her tireless ambition to make teaching a more human, dynamic and understandable task. Similarly, her inventions were geared towards improving educational methods: a new typewriting system (simpler than the one used up to that time), along with a typewriting machine; the Grammatical Atlas (which was accepted by the Spanish Royal Academy) and, most importantly, the Mechanical Encyclopaedia. All of them were notable for the implementation of educational concepts which, today, stand out for their modern approach. Up until 1975, the year of her death, Doña Angelita was still paying the fees for the patent of the mechanical book that she was granted in 1962, a demonstration of her firm conviction that another way of teaching and learning was achievable.

Doña Angelita and the mechanical books

Doña Angelita was granted her first patent in 1949 for “a mechanical, electrical and pressurized air procedure for reading books.” Designed for students, it represented a new way of viewing a textbook. In this ‘book’ the subjects were activated, bringing them to the forefront of the device by buttons; others, meanwhile, allowed the book to be illuminated, making it possible to increase the size of the text and even write and draw on it. There was even the possibility of using luminescent inks so it could be read in the dark. This ingenious device could be manufactured in different sizes and shapes: characters from popular children’s stories, plants or toys. The teacher’s mind was always busy with ideas for transforming and innovating education. The affection and respect she felt for her pupils led her to seek out ways of improving their school life and facilitating the learning process. The saying “to spare the rod is to spoil the child”, so prevalent at that time, did not even enter her educational mind-set.

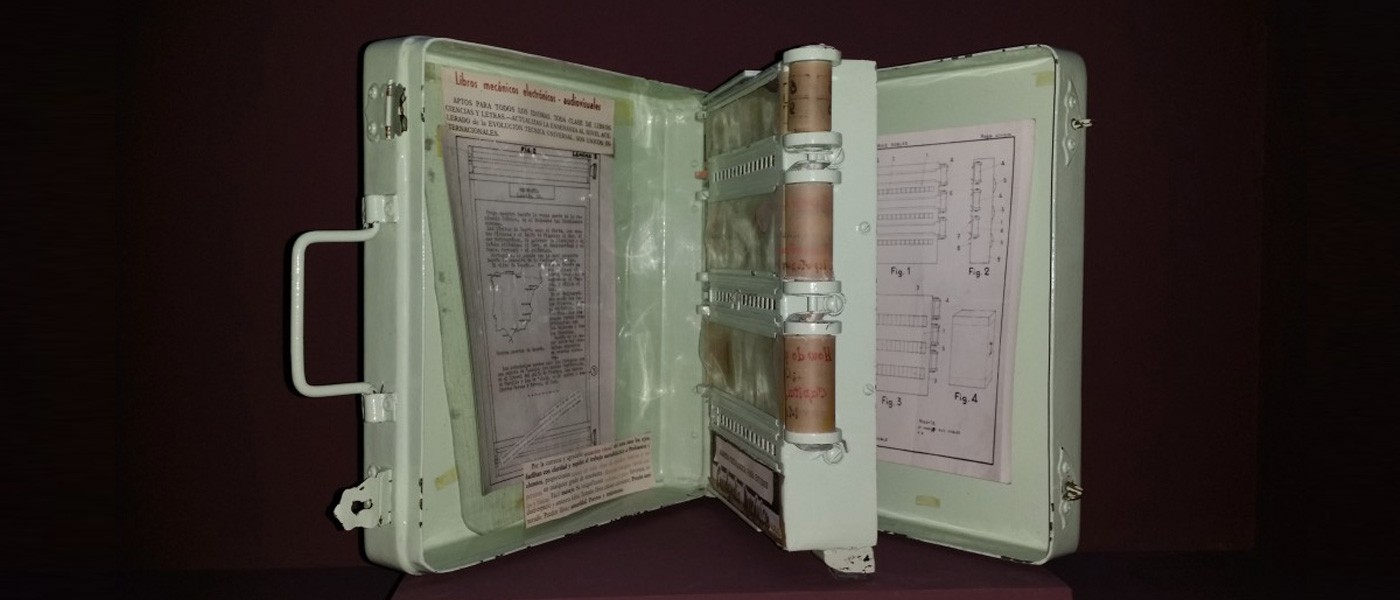

Within this idea for electronic books came Doña Angelita’s most ambitious project yet: the Mechanical Encyclopaedia, a device that would include all the student’s subjects and tasks. It would open like a traditional book, and on the left there would be a series of automatic spellers that would let you form sentences, phrases, etc. On the right the subjects would be arranged, presented on separate, interchangeable cartridges. Compact, made from lightweight materials and with a little carrying case, the student would bring it to school along with whatever cartridges were necessary for that day’s subjects. It would also include a light, luminescent inks and a magnifying glass to read the texts. Interactive, accessible, practical and logical, the Mechanical Encyclopaedia could help even the most recalcitrant student. Doña Angelita’s tireless quest meant that she continued to pay the patent fees up until 1961. The following year she applied for a new patent for a similar, though somewhat more simplified, device.

A device for reading and different exercises

The encyclopaedia on display is the prototype that was built after the second patent application, in 1962. Given the impossibility of the original project for the Mechanical Encyclopaedia, Ángela Ruiz Robles applied for another patent for a “device for reading and different exercises”, a simplified version of the original idea. The whole system of mechanical or electrical buttons was eliminated, and with it the moving parts and elements, in order to make the resulting mechanism as simple as possible for this second patent application. The second design features a compact block on whose front the spellers and the cartridges containing the subjects could be fitted, thus keeping the original idea of being able to change subjects on a single device without having to bring a different textbook for each subject to class. In the patent application, Doña Angelita described a carrycase for transporting the encyclopaedia which also included space for cartridges for other subjects and exercises, and for an audio player to allow students to listen to lessons.

The prototype on display here was built at the El Ferrol Artillery Depot according to instructions from Doña Angelita and at the orders of Major General Constantino Lobo Montero, the honorary mayor of the city. Although the book you can see here was made from metal, in the teacher’s mind it would have been made from more lightweight materials such as plastic or nylon, making it even easier for students to carry. In 1971, the Technical Institute of Applied Mechanical Experts (ITEMASA) conducted a study on the feasibility of manufacturing the device, although it didn’t get as far as making a prototype. It seems that the sum of 100,000 pesetas at that time was quite a deterrent to its manufacture.

A bridge to electronic books

Doña Angelita kept up the payment of her patent fees until 1975, the year of her death, and never lost hope of seeing her mechanical book brought to life; of facilitating an easier, more visual and appealing learning process based on the idea that it would be more user-friendly and accessible to students. Doña Angelita’s merit goes much further than the invention of a mechanical book with buttons and lighting. Its importance lies in her capacity to think in a different way; to tackle a problem by thinking outside the box, coming up with a solution that went beyond the logic and technological potential of those times or the ability of society to understand and accept it. Ángela Ruiz Robles, in her determination to educate and to make learning easier, devised an artefact that was impossible to implement at that time, and which perhaps people did not want to accept, with a brand new conception of a textbook, a new reading support, an innovative format. A book that was not a book, a notebook without pages, a tactile and interactive device, an encyclopaedia that would bring together all the knowledge of that time in a single place… sound familiar? The Mechanical Encyclopaedia deserves a place of honour in the genealogy of electronic books that emerged several decades later. Doña Angelita was undoubtedly one of their pioneers.