Did you know that the Telefónica building was the first skyscraper to be built in Spain? It was also the tallest building in Europe for a number of years. And do you know the name of its architect? Yes, it’s Ignacio de Cárdenas.

Did you know that the Telefónica building was the first skyscraper to be built in Spain? It was also the tallest building in Europe for a number of years. And do you know the name of its architect? Yes, it’s Ignacio de Cárdenas.

The Telefónica building on Gran Vía has borne witness to the passing years ever since Madrid languished at its feet back in the 1920s. From the towering height of this American-style skyscraper it has watched how the technology rolled out by this new company, Telefónica, connected the whole country by the most revolutionary inventions of that time.

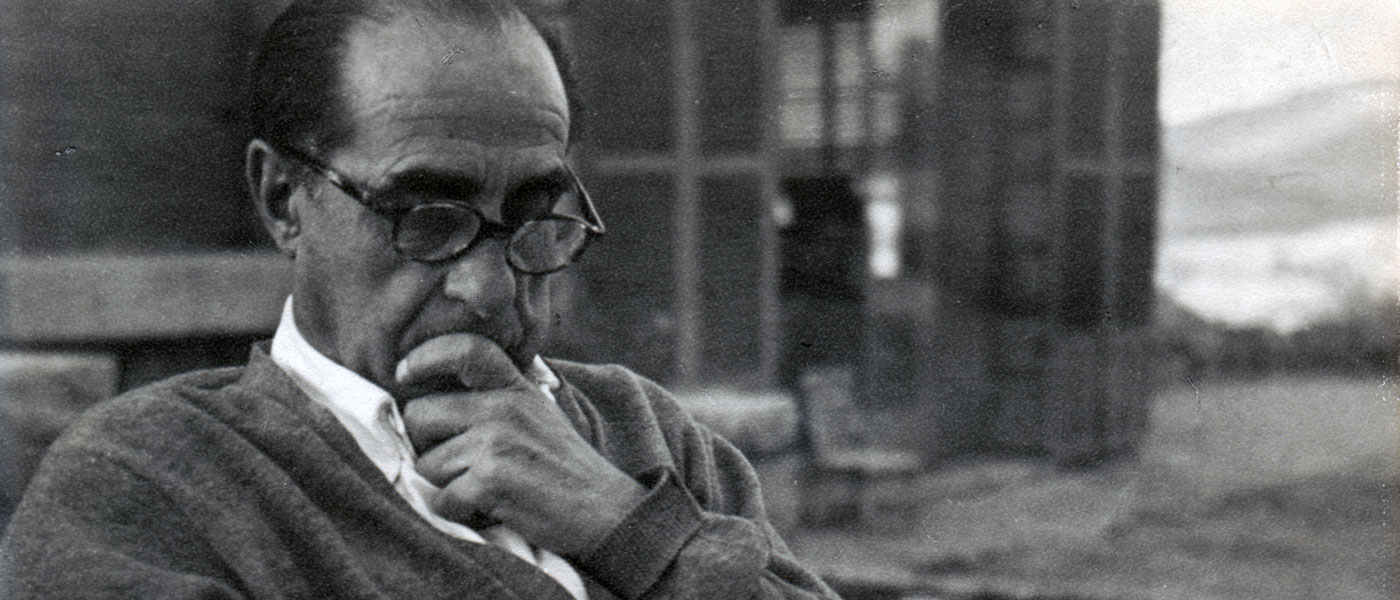

This exhibition aims to reveal the origin of the Telefónica building and, most importantly, talk about the architect who conceived, designed, built and maintained it: Ignacio de Cárdenas. An intrepid architect who ruined his health in the building, “living in it during the war, withstanding the gunshots that couldn’t bring it down’.

As well as designing the Gran Vía headquarters, Cárdenas was also the head of the Building Department of Telefónica from the late 1920s and into the 1930s. This department was responsible for building no fewer than 42 switchboards in record time, which entailed a huge amount of organization and coordination by the architect, who completed his studies the same year as he was taken on by Telefónica.

A lot of what is related in the exhibition is based on the ‘Notes for my Memoirs’ which Cárdenas wrote over the years: recollections, anecdotes, impressions… which his family has very kindly allowed us to transcribe and use as a guide for the exhibition.

An interesting selection of family photos of Ignacio de Cárdenas, personal objects, sketchbooks and excerpts from the notes that chronicle the life and work of this pioneering architect is rounded off by magazines and graphic material from Telefónica’s own document archive.

Spain in the Twenties

Ignacio de Cárdenas Pastor was born in Madrid in 1898, the year that Spain lost Cuba. The last-but-one of 16 children, while he was studying architecture he was called up to fight in the Spanish war against Morocco. It was in this Spain, mired in a permanent political crisis, that he grew up.

The conflict in Africa, the reign of Alfonso XIII, the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera… this was an era that portended great change, in a society of great gulfs. The anarchist movement took deep root among the poorer communities and the army made desperate attempts to coalesce this deeply fragmented and polarized society.

In 1924, Cárdenas achieved his degree as an architect. That same year, in April, the National Telephone Company of Spain (CTNE) was founded. Created by the ITT along with Spanish investors, just four months later it signed a contract with the Spanish State to reorganise, reform and enlarge the national telephone service which up until that time had been divided into different companies of varying sizes with numerous owners (both public and private). It was at this time that Ignacio de Cárdenas managed to get an interview with Telefónica, which was looking for an architect, and was recruited by the company.

The architect relates in his notes how at the beginning of 1926, Sosthenes Behn –the president of ITT – asked him who he regarded as the best Spanish architect to take on this project. Having suggested various names, he then mentioned Juan Moya, who had also been recommended by the Duke of Alba. A former teacher of Cárdenas, he had a well-established track record and enjoyed great renown, as well as being the architect of the Palace. Moya finally won the commission and asked for Cárdenas to be involved in the design as well. Moya’s design for the building, which was very baroque and ornate, did not meet with the company’s approval, while Cárdenas´ sketches did please Behn: “In a very short time, Colonel Behn had decided that I should be the person responsible for undertaking the Gran Vía project,” writes Cárdenas.

Work gets underway

In October 1926, work started on the Telefónica building on Gran Vía following the construction system of American skyscrapers, its skeleton of riveted steel struts rising up in the midst of Madrid. It was completed in record time: in 1928, the switchboard was already operational to connect the first transatlantic call between Madrid and New York, which was attended by King Alfonso XIII and the senior management of ITT and CTNE.

The work was officially completed on 1 January 1930. The head office of Telefónica, intended to “seduce the shareholders”, as Sosthenes Behn put it, astonished the people of Madrid. The country’s first skyscraper and the tallest building in Europe at that time would from then on be the headquarters of Telefónica.

A stalwart building

In 1936 the country would be plunged into a Civil War that would last for three interminable years. Madrid, on the Republican side, would be besieged until its total submission. The Gran Vía became known as the Avenue of Shells… and as its highest point, the Telefónica building rose up above all the other Madrid buildings and served as a perfect target to guide the shots of the Nationalist army.

Cárdenas tirelessly visited “his Telefónica”, keeping a record on a map of the artillery hits which left traces all over the building, especially on the façade on Calle Valverde. The building managed to withstand the artillery and inside the switchboard continued operating. The foreign correspondents, holed up in the former Hotel Florida de Callao, used to come to its offices to send their war reports.

The architect fell ill in 1938 before the war ended. Tuberculosis forced him to move his family to the Haute Savoie region in search of a cure. Cárdenas was still in Savoie when the end of the Civil War was announced. However, the country’s situation and his own circumspection made an immediate return unadvisable. He spent a few years in France, finally returning in 1944 once he was sure of his safety. Even so, he was punished with “perpetual disqualification from public office, management positions and other positions of trust, and disqualification for five years from the private practice of his profession.”

Cárdenas did not return to work at Telefónica but joined the construction company Gamboa y Domingo and designed various projects with his nephew, Gonzalo de Cárdenas. These included the Bancaya building, built between 1947 and 1953 and popularly known as the Iberia Building due to the illuminated sign on its roof. Other projects, such as No. 63 Calle Zurbano, would follow, and in the 1960s he became the municipal architect of El Espinar, in Segovia, where he died in 1979.

The extension

The relationship between Cárdenas and the building did not end with the Civil War. The extension undertaken in the 1950s was done following his original plans and in 1955, at last, the building stood on Gran Vía just as he had designed it. A skyscraper in the American style, “imposing, strong and majestic.” And from its 89.30 metres it has dominated the city of Madrid ever since.

The building always filled him with pride, as he recorded in his notes in 1970: “71 years already! […] After all these years, I remember very few things that made my heart beat as strongly! I remember how excited I was for a few moments […] perhaps the view of Madrid from the train on that 13 June 1944, when I returned from France with a rookie cop at my side… and to see my Telefónica building had held firm against all the disasters of war.”

You can visit the exhibition Ignacio de Cárdenas, a pioneering architect on the second floor of the Espacio Fundación Telefónica between 22 March and 18 September 2016.